school skool, n. a place for instruction: an institution for education, esp. primary or secondary, or for teaching special subjects: a division of such an institution: a building or room used for that purpose: the work of a school: the time given to it: the body of pupils of a school: the disciples of a particular teacher: those who hold a common tradition

gallery gal’a-ri, n. a covered walk: a long balcony: a long passage: an upper floor of seats, esp. in a theatre, the highest: the occupants of the gallery: a body of spectators: a room for exhibition of the works of art

School Art (Welling) School Art

Art classrooms in schools are brimming with art works. Piled high on every surface, stuffed into plan chest drawers, stapled to the walls against a background of fading sugar paper, gathering dust on shelves. Every day during the school year, this ‘collection’ is added to, until in the last few weeks of the summer term students select the things they want to keep to take home, and bin bags are filled with much of the rest to make room for the following academic year’s mass of efforts.

The creation of art is impossible without the consideration of an audience. In the case of much of the work produced in schools this audience, at least initially, is the teacher; the evidence of their appreciation or understanding in the grade that the student receives. But how often are school art works created with an understanding of the context in which their creator wishes them to be seen?

My school is fortunate enough to house a dedicated gallery (The Berwick Road Gallery). Having a gallery as part of the school buildings means that this consideration of context and display is an integral aspect of the manner in which students go about making work. Since 2000, when the Arts Centre that houses the gallery opened, we have established an exciting programme of exhibitions that have included touring shows from the Arts Council, such as Goya’s etchings, prints by Joseph Albers and the photographs of Walker Evans. Alongside this we have focused, predominantly, on exhibiting the work of the students themselves.

Arguably the highlight of the gallery calendar is our annual alTURNERtive Prize exhibition, which takes place towards the end of November each year. The award was founded in 2002, celebrating the school achieving status as a visual arts specialist school. Taking its cue from the Tate’s Turner Prize, the intention was to celebrate and showcase some of the outstanding practice being undertaken by students in the upper school. Each year a small number of students are selected; a complex process that involves all members of the visual arts faculty making nominations before we decide on a final shortlist. The exhibition is then considered by a panel, that since 2004, has included an external judge, and on the opening night we invite an eminent artist, critic or curator to announce the year’s winner.

The alTURNERtive Prize has established a considerable reputation and is visited by significant numbers each year, but its most important role is in the way in which it has impacted on the approaches that students take in the classroom. Having a gallery on site means that the students’ awareness of the role that context and display has on the potential meanings for their works is an essential part of the work itself. Whilst the alTURNERtive Prize now has an engine driving it each year; a full colour professionally produced catalogue; accompanying documentary film interviewing the shortlisted students; and a budget to ensure that the work is realised to its full potential, the use of the gallery has developed in an arguably much more interesting way outside of these organised formal exhibitions.

Students are now very conscious of the role that exhibiting their work has, both in terms of audience and the consideration they need to take when planning how work will be seen. More and more, the gallery is used by the students as a forum for presenting ideas, a place where work can be exposed for discussion and debate. Their familiarity with the space, the ease with which they take work into it, present ideas in a professional manner, document them, alter them, and encourage responses from an audience, has completely transformed the ways in which they approach the practice of making art. No longer are they creating things in a vacuum. Their work is intrinsically linked to its reading by others. We are encouraging them to place importance on how their work will be perceived, to incorporate an understanding of its possible meaning into the development of their ideas. Indeed it has become essential for us to ensure that the gallery has periods when it is ‘unoccupied’ in order to allow students the possibility of utilising the space. These ‘guerrilla’ exhibitions are often the most exciting.

The faculty of Visual Arts at Welling School may be distinguished from other visual arts faculties by the emphasis that it places on the framing and meditation on art and the ideas that surround it, as opposed to its production. This emphasis on context enables the students to develop a sophisticated understanding of the possible meanings of the things they are doing.

The alTURNERtive Prize – A Brief History

Regardless of one’s opinion on the Turner Prize it is impossible to deny its incredible impact and contribution it has made to broaden the appeal of contemporary art in this country. When I was at school I knew of no one who was alive and working as an artist. The Turner Prize changed all that. I remember a cartoon in a tabloid newspaper in the 1990s that depicted John Major floating in a tank with the tag line “The Physical Impossibility of Winning Another Election”. The assumption being that the readers would ‘get’ the reference to Damian Hirst.

In 2002, partly to celebrate becoming a Specialist Art School, and partly because the gallery was there and should be being used, we established the alTURNERtive Prize, an annual awards exhibition that celebrated the very best of the work the students were making and linked to the Turner Prize.

2002

In that first year we selected a group of students from years 11, 12 and 13 and chose a piece of work from each of them. We put together an exhibition, produced voting forms and I took all my own classes, and then groups from colleagues, into the gallery and asked them to vote for their favourite piece. The exhibition included a fantastic range of work, from painting; a self-portrait, after Vermeer, by Louise Hoyne-Butler, to sculpture, Nick Lockyer’s piece involving plaster covered discarded clothes and Nathan Gooding’s disturbing life size figure undergoing an operation. In the end it was after Christmas before we had counted the votes and selected a winner: A year 11 student, Toni Wilson, who had shown a video piece she had made that involved a slowed down film of the playground, shot early in the morning, in which she had painted the outline of a friend’s body, looking like a murder scene from a TV drama.

2003

The following year saw a very different approach to the exhibition and, in many ways, was the true beginning of the alTURNERtive Prize. We selected a much smaller shortlist and met with the students to discuss with them what they would like to submit. It gave rise to the opportunity to introduce notions about display and context, something that was not really touched on in our teaching at this point. They were invited to show more than one piece of work if they wished or could make something specifically for the exhibition. The exhibition was a strong one and included some memorable pieces. Steven Bayliss showed a hovering landscape constructed from woven cotton buds, Samantha Lovell showed a series of thickly painted copies of soft porn photographs from lads’ mags and Nicky Field, the eventual winner, submitted linked pieces of work including an incredible 5ft square self-portrait, created with the use of 10000 fingerprints that had taken him almost a year to complete and a wall based piece involving the use of 1500 elastic bands stretched in a perfect circle around a nail.

In an effort to move away from a populist vote and ape the Turner Prize further, we invited a panel of judges, Paul Dash from Goldsmiths University and a recently employed colleague to make up the third member of the new panel, along with myself. This was the first year that we interviewed the shortlisted students on film, creating a short documentary, which we screened at a private view, something that we have continued to do every year since.

2004

The shortlist in 2004 was set at 12 students, a formula we have followed ever since, with the exception of one year. Again students were chosen from the upper three years of the school. The exhibition included a very broad range of practice once more, and had a distinctly different feel to the preceding year. One of the noticeable things about the alTURNERtive prize has been the way in which each year is so different. Far from showcasing a Welling School ‘house-style’, the exhibition demonstrates the evolving interests of the faculty and the individual interests and obsessions of the participating students. Several works stood out. In particular, Emily Bell’s striking silent movie depicting the horrors of back street abortions. The award was won by Holly Coventry who had included a video piece that depicted herself sitting up and falling asleep, sped up to create a disconcerting effect. For the first time, we invited what was to become known as a lay judge, to join the panel; one of the deputy head teachers.

2005

In 2005, at the private view of a 6th form exhibition entitled “Happy Days”, a man arrived in jogging gear and began to look around. I assumed the jogging man was someone’s father and began to speak to him. It turned out that he wasn’t connected to the school at all, but that his friend Richard had sent him, also sending his apologies for not being able to come himself. I realised that he meant Richard Wentworth. I had been lecturing at the Tate Modern the week before and Richard had been one of the other seakers. I’d taken the opportunity to invite him along to the private view. Talking a little more about the exhibition, and how he had come to be sent there, I realised that I was speaking to the art critic and writer Michael Archer, then Dean of The Ruskin School of Drawing at Oxford University. Michael was very impressed with the exhibition and interested in what we were doing. We spoke for some time about the alTURNERtive Prize and I asked him if he would be prepared to be a judge for the next one. He said he would love to, and then went on, to my amazement, to explain that it would be a very interesting experience for him, having judged the Turner Prize itself in 2002. I couldn’t believe it and in a flurry of confidence wondered whether he thought Richard would be happy to present the award. He thought that he’d love to and suggested I ask him. I did, and he did. So in 2005 the alTURNERtive Prize at Welling School was judged by an ex-Turner prize judge and presented by an internationally renowned artist.

The exhibition included David Lockyer’s striking, tiny pencil portrait of Adolf Hitler, Iain Ball’s tongue-in-cheek re-make of a Duchamp readymade, alongside Kate Lovell, the eventual winner, who showed two sculptural self-portraits; one constructed from a dismantled umbrella and a self-supporting dress constructed entirely from zips. This year was the first time that we produced an accompanying catalogue, including brief explanations about the students’ work.

2006

In 2006 Lucy Davis, the director of the 198 Gallery, presented the award. The show saw another broad range of practices and included Chris Croft’s hanging Perspex sheet, distorted with a blow torch, Rajinder Dhillon’s meticulously constructed paper-cuts, George Dunsford’s circle of wax figures complete with chicken bone skeletons and Jon Long’s expressive process paintings. The judges chose Jon Long.

2007

Kelly Worwood, from the Tate, joined our judging panel in 2007. It proved impossible to shortlist to twelve and we ended up showing thirteen students in another exceptional exhibition, including Billy Granger’s glittering gold BMX and a neon pink haystack, Kelsey Giles’ amorphic pile of stuffed tights, Victoria Norton’s series of family photos that she had carefully scratched herself from, and Rachel Robertson, who was awarded the prize, showing emotionally powerful pieces including a video of a chocolate sculpture cast of a breast being slowly devoured and an installation of curtains of burnt toilet paper.

2008

Howard Hollands, from Middlesex University joined us as a judge and Joseph Smith was our winner in 2008. He displayed an empty blackboard upon which he had been drawing, and then erasing, portraits of his deceased relatives. Also in the exhibition was Emma Gower’s bed cover constructed from knitted condoms, Laura Debourde’s diary of 365 photographic self-portraits, taken over a year, and Laura Lloyd’s beautiful projection of a shadow passing slowly across a wall. The artist, Hew Locke, presented the award.

2009

Ryan Gander presented the award to Layla Fay for her poignant collection of exercise books, documenting the development of her literacy skills from nursery to GCSE English. It had been a very difficult year to judge with Layla facing stiff competition from Jordan Kidman, who exhibited an ambitious installation including photographs and artefacts taken from an abandoned mental asylum, as well as films made using found footage showing experiments on mental patients, and Emily Prestidge who showed a diary of a month’s worth of found objects displayed in test tubes.

2010

The tradition of school-related work following on from the blackboard piece in 2008, and the exercise books in 2009, continued in 2010. Camilla Price was awarded the prize for her installation that included a pew carved by the boys’ school in the 1950s, the actual school registers from the same period, and audio pieces she had made whilst interviewing ex-students from the girls’ school. The exhibition included other extremely ambitious work, in particular Gemma Gibson’s creation of the Apartment of Jean Noir. In it, Gemma had constructed a hallway from the flat of an imaginary French photographer, complete with his work, belongings, clothing and, even smells. The critic, Ben Lewis, was our guest presenter.

2011

The artist Anna Barriball joined us as a judge. Danielle Leigh exhibited an abandoned piano that she had manipulated using found materials to create a unique instrument inviting the visitors to interact with and play it; she included a score written specifically for this purpose. Vanessa Harrison worked with the fabric of the gallery itself, creating sagging sections of the walls. The eventual winner was Tiffany Webster. Tiffany showed a mesmeric film of inks falling into water, slowed down and reversed to a spellbinding effect. Alongside this she displayed a series of delicate wax sculptures, three-dimensional manifestations of the film made by dropping hot melted wax into cold water. Another artist, Eleanor Crook, presented the prize.

2012

For the second time since the founding of the award, we invited an ex-student and ex-participant in the alTURNERtive prize, to be a member of the judging panel; Laura Lloyd, who had been in the 2008 exhibition. She joined Andy Berriman, an ex-head of art from Welling School, and Amy Green, a new languages teacher. The exhibition showcased a broad range of work once again, with Holly Gibson winning for her taxonomical installation of her experiments with chemistry and casting. The artist Harold Offeh, who we had been working with in collaboration with the Tate Modern, presented the award.

The alTURNERtive Prize has raised and continues to raise, the profile of the visual arts within the school. Posters go up in the weeks preceding the exhibition and younger students are able to spot their older peers on the poster. You can overhear discussions about the show happening and once it has opened we take the other years in during lessons and also open the gallery at lunchtimes. It is well attended. The exhibition represents something to aspire to. It places an emphasis on ideas of display, and indeed of audience.

From it’s inauspicious beginnings it has grown into a beacon in the school calendar and to a widely recognised and significant event in contemporary art education. When Ryan Gander presented the award in 2009 he commented on how mature and sophisticated the work was, praising the students for the eloquence with which they discussed their practice and suggested that his MA students could learn from them. Ben Lewis, when writing a review of the exhibition after having presented the award in 2010, wrote “I was confronted with some of the most precisely-formulated and witty contemporary art I had seen in London in months”.

School as Museum

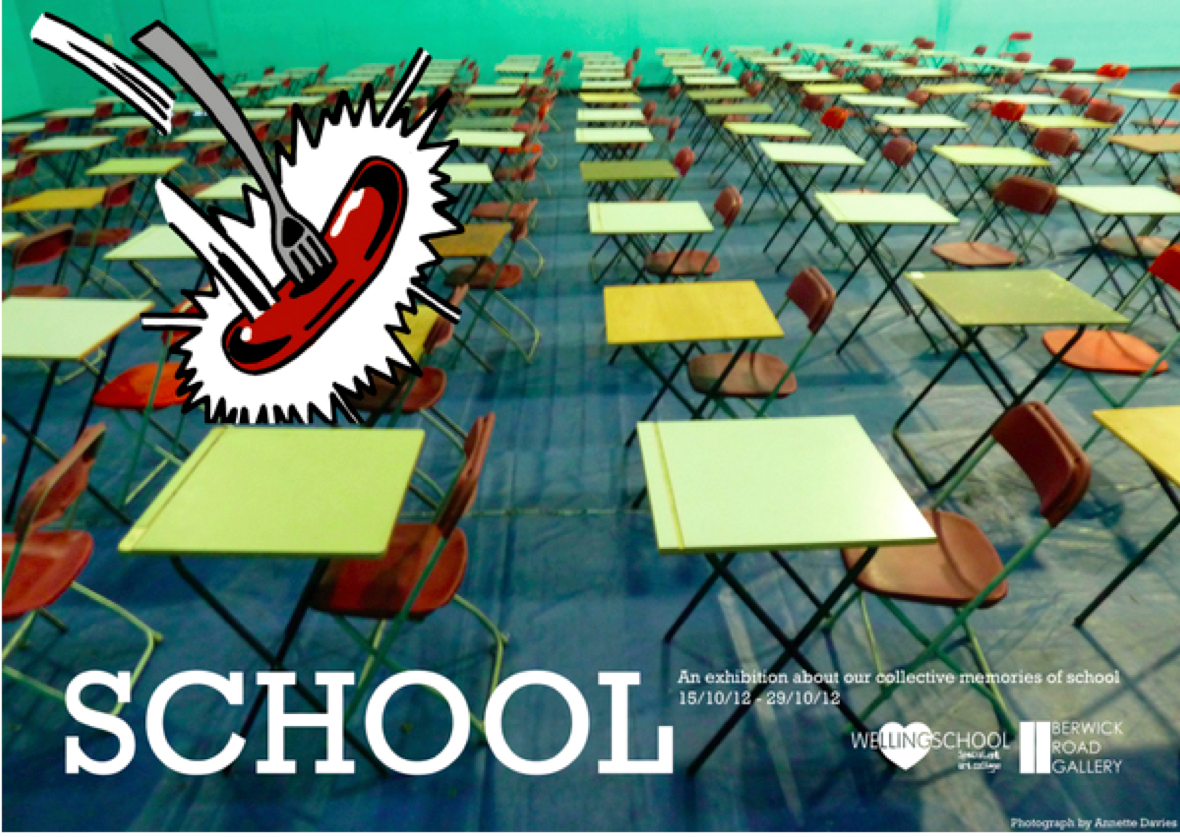

The gallery is such a vital part of daily life within Welling School. In 2012 we decided to use the space to create a museum of school life, an exhibition that was a literal manifestation of collective memory: School as Museum.

Much of the developing practice within the visual arts faculty has been around the notion of work addressing where we are and who we are, of encouraging students and staff to engage with the situation they find themselves in, that of studying or working in a school, and to make work that responds to this. The exhibition would celebrate this approach at the same time as collecting together the artefacts and materials generated by the daily life of a school.

A couple of years before, one of the 6th form students, Camilla Price, had produced an extensive project about the school’s history. The project had started inadvertently. One afternoon, I had decided to take the class on a walk instead of spending our lesson in the classroom. The students kept their coats on and armed themselves with notebooks, pens and cameras, and off we went. I wanted to explore areas of the school site that they were not usually privy to and for us to walk, talk and think and see what might happen. At one point we found ourselves in a corridor that is normally restricted to staff only. There was a display of photographs from the school’s history; sports teams, the old school buildings, class groups; the students were fascinated, particularly Camilla.

The following day she came to see me to ask whether she could have access to the photos, as she wanted to develop some ideas around the school’s past. I sent her off to find a caretaker and when she returned, some time later, she revealed that she had been taken to the school’s archive and allowed to explore it. I had no idea we even had an archive. The work that Camilla made over the following months was beautiful. She ended up researching the 1950s, a period when the school had been located in separate girls’ and boys’ sites, and decided to track down some of the students that had attended at that time. Her resulting pieces; a series of audio interviews with women who had been students back then, were incredibly moving and sophisticated, highlighting both how much the had school had changed at the same time as showing the enormous similarities.

Here was the seed of an idea. All schools keep records. Hidden away in cupboards, like our own neglected archive, these records, this ‘museum’, needed to be made more public. So the idea for an exhibition that presented this came about.

We decided to present objects from the history of the school; photographs, documents, and, most fascinating of all; the school log book, a record of events kept daily by the head teacher from the 1930s to 1973 (when daily events became too numerous to record). The log book contained some incredible entries, perhaps one of the most memorable; “Unexploded bomb fell on school field. Start of school delayed. All clear by 10am”. Alongside these historical artefacts, we presented the personal histories of those people that make up a school. A school is, after all, a group of people as well as an institution. We invited staff to record their memories of their own schooling. Many provided photographs, school reports and their school books. We had a display of teachers’ old school ties. Students were also involved. Several students made pieces of work that directly responded to the idea of ‘school’. One interesting installation being a collaborative piece by two year 11 students who had carefully removed all the discarded chewing gum from underneath the desks in a math’s classroom and presented it as an organised grid in the gallery.

The exhibition was an enormous success. Everyday different people from the school community came to visit it and to spend time reading through the material. School is something that everyone has in common. It gives us a common language and this school museum allowed us to reflect on what that means.

Reflective Washing Lines & Shanty Town Studios

Art classrooms are seldom perceived in the same way as other school classrooms. Art classrooms are often the spaces in which students seek refuge from the mundane and characterless environments of the remainder of their timetables. But art classrooms seldom enable students to have ownership over the space they inhabit. The pressures of a school timetable, with its bells and periods and students constantly on the move, means that quiet spaces for genuine contemplation are hard to come by. The experience I remember enjoying once I had arrived at art college and was given a studio, albeit a very small one, in which to work is beyond the expectations of a secondary school art student.

I wanted to change the way in which my classroom, or studio, was operating. At the time I had a GCSE class that were reluctant to engage with one another. It wasn’t that they didn’t like one another, more a case of not really knowing one another and being happy to operate in parallel rather than engage in any kind of dialogic activity. I decided to present them with an obstacle, something physical that they would need to negotiate. I prepared the space by dividing it into several ‘separate’ studio spaces, each delineated by string. Each ‘studio’ was allocated to a student from the group and I indicated this by hanging a name-tag on the string. When the students arrived for their lesson the next morning they were confronted by an obstacle course of string barriers that they had to climb over or duck under in order to find their own space. It had an immediate effect, in that they began to relax and enjoy themselves in a different way. Once they had arrived in their spaces I explained that they had to remain within their string studio for the rest of the double lesson; they could only use the materials and facilities within their given space, but, if they wanted something from somewhere else, they would need to negotiate this with their neighbour. So for example, if they needed to research something on the internet and the computer was in a space on the other side of the room, they would need to ask the student in their neighbouring space to pass the message on and they, in turn, would need to ask the person next to them and so on.

The structure of the lesson, and the physical structure of the space, had a profound effect on the way in which the students were making work and developing their ideas. The dynamics of the class and the group changed completely.

Feeling that something significant was happening I decided to utilise the string divisions in another way. They bore an obvious similarity to a washing line and so, seizing the opportunity, I asked the students to use these ‘washing lines’ to display something for us to discuss. They were instructed to go through their sketchbooks and the work they had been making, and to choose several things that they were prepared to hang up for the rest of the class to look at and discuss. To literally, air their (dirty) washing.

It resulted in some very interesting outcomes. One student, during the crit that concluded the lesson, recognised for the first time an obsessive interest in using text within her work. It was revelatory. For the first time with the group there was a genuine interest and engagement with one another’s work and ideas.

I wanted to develop what had happened further still. The school had recently invested in interactive whiteboards for every classroom and this had generated an enormous number of cardboard boxes. Working after school one evening, I converted my classroom into a warren of cardboard rooms; shanty-town studios. The transformation of the space was profound. Over the next few days I taught in this new space, with students operating within their own small studios. It meant that the 6th formers had spaces of their own and they quickly began to embellish and alter the spaces, adding doors and letter boxes, in order to pass messages to one another; making their spaces more private or interacting with the fabric of the space itself to install their work. When the GCSE group returned they were mostly required to share spaces. This created interesting dynamics and several students immediately embraced the idea of working collaboratively. Again there was a natural urge to work with the actual spaces themselves. The student who had discovered through the ‘Washing Lines’ a tendency to use text, began to write directly on the walls of her ‘studio’ creating a very personal diary. Two other students set about constructing a ‘film set-inspired’ environment, using more of the recycled cardboard.

Changing the spaces changed the way that the students engaged with space itself. Instead of arriving in the classroom ready to follow a set of instructions, sitting placidly at a desk, they embraced the space and interacted with it directly.

Gold Plugs and a Minotaur

Working with the art classrooms themselves as ‘potential material’ has changed the way in which students think about their work. One of the most interesting developments has been the way in which students have begun to look at the school environment as a whole and the potential that it presents for creating installation and performative pieces of work.

As a specialist arts school there is an inevitable expectation that the whole school display will reflect the work that goes on in the arts faculty. The corridors are full of a regularly changing selection of framed work. But the most interesting aspect of school display has been the development over the last few years of more subversive interactions with the environment from the students themselves. Because of the enormous emphasis on context, and the encouragement that we give to think about space and how it might be used, students have begun to work directly with the fabric of the school. This is not without its problems.

A number of years ago one student began replacing electrical plugs with ones he had spray painted with gold paint. The intervention was subtle. It was some considerable time before even his art teachers noticed what he was up to, but it had interesting implications. Schools, like any other institution, are fastidious about the necessary health and safety requirements, especially where electrical equipment is concerned. Here was a student who was completely flouting these rules and yet creating very beautiful objects that almost no one was even noticing.

Several years ago the school was largely rebuilt under a PFI scheme, where the local council negotiated a deal with a private company to rebuild the school in return for the company then leasing the buildings back to the school for a period of 25 years. Consequently we no longer own our own building and this has generated significant problems with regard to the ways in which art students intervene with the spaces. Recently this resulted in an interesting stand off following a piece of work by one of our year 12 students. She had been working with chalk in the playground, creating enormous text pieces with the positive message of “I Want an A”. The owners of the building took issue with this, stating that we were encouraging graffiti and vandalism and that the art faculty were irresponsible. The irony of her use of chalk with its inevitable connections to ‘education’, and the positivity of her message had completely escaped them.

More recently a year 10 student has been cladding parts of one of the art classrooms entirely in tin foil, creating a fragile but extremely beautiful new space. Her embellishment covered walls, parts of the ceiling and some of the furniture, rendering the classroom a little difficult to teach in. The impact such interventions have on other students cannot be underestimated. The questions that are provoked are incredibly valuable.

One of the other developments has been the embracing of more performative approaches to practice. The school has a light well near the administrative offices. A few years ago one of the 6th formers decided to use the space for a performance. He constructed a minotaur costume, completely hiding his identity, and stood silently and still in the space, awaiting the bell that indicated it was the beginning of break time. Upon the bell, scores of students began to pass the light well on their way to and from their lessons. The minotaur stood completely still, appearing as though a sculpture rather than a person dressed up. His presence caused inevitable interest with students pressing their faces up against the glass. Once he had a big enough crowd, he ran towards them causing considerable shock and interest.

He went on to spend other times in costume, including taking advantage of snowy weather and heading off to the nearby woods where he ‘lived as a mythical creature’ and employed some of his fellow students to document his project in video and photographs.

Such activities, the norm for arts institutions, galleries and museums, have become an accepted part of life at the school. Instead of the question being ‘is it art?’ it has become ‘it is art but what does it mean?’ surely a much more interesting proposition.

The definitions at the opening of this volume suggest that a school is an institution for education and that a gallery is a room for exhibition of the works of art. I would present the case that the definitions are not mutually exclusive. Welling School is a gallery. Galleries are educational institutions.