Introduction

I am standing in a school art and design studio. Around the floor in front of me are the outcomes of a year 12 examination, the results of two days’ intensive labour: paintings, sculpture, collages and photography. At the back of the room, a chicken wire model inspired by the Tower of London rises from a base made of garden turf. Pinned to the wall is a series of police evidence bags, each containing a small object or photograph and accompanying text. On one table is a series of beautifully composed photographs depicting the storyboard of a rail crash. Closer inspection reveals that each photograph is taken from a carefully constructed miniature set-up, using model railway buildings, train carriages and people. At the other end of the room is a standard globe, as found in every geography classroom. There is a sickly sweet smell surrounding it. Every single country on the globe has been modelled in chewed bubble gum and chewing gum, creating a surreal and disturbing alternative landscape. The pupils were required to respond to a brief about the city, to create works inspired by cities and the idea of creeping urbanisation.

Contemporary practice is having a profound effect on our pupils. If I think back to my own art education I can only remember drawing spider plants or still life set ups of deodorant bottles and pairs of trainers. I had no idea it was possible to be an artist. I had no conception that there were people making art. Art was something that happened in history. I couldn’t see a possibility to make art which truly reflected my own feelings and ideas. But this is changing. I think that the high profile contemporary art has acquired over the past decade, particularly in the UK, is giving us, as educators, a fantastic opportunity to alter the way we teach.

Welling school, where I teach, is a sprawling co-educational secondary school on the outskirts of London. It is non-selective, but the borough operates a selective system, so the top 20% of children are creamed off at the age of eleven by the local grammar schools and we are left with the rest. Two years ago, after a long and protracted process, the school gained specialist status (1) in the visual arts. At the moment we are functioning on a building site while the school is being extensively re-built as part of the PFI (2) initiative. This is where I teach alongside five other colleagues and artists in what is a dynamic and stimulating teaching and learning environment.

I Can’t Draw

I’m stood in a room full of adults and I’ve just asked everyone who feels they can’t draw to raise their hands. I’m looking at a sea of hands. I guarantee that every single one of those individuals drew something before they could write or even speak. Drawing was one of their first forms of communication – an argument, then, for a back to basics approach, a skills led approach? Well I don’t think so.

Inspiration (can be found) in drawings by children, where innocence of conventional skills has allowed freedom of expression all too often denied the professional artist by his or her formal training. What an irony, if drawings by untrained people are more likely to offer fresh insights and idiosyncratic vitality than drawings by professional artists. But the untrained have no value for what they themselves can do. They, God help us! Would like to draw like Leonardo! (Oxlade, 2001)

No my plea is for an art education that gives people faith in their own means of expression. That gives them the facility to express themselves visually. That lets them know that what they make is valid.

Genre Photographic Portraits with Year 7

Since acquiring our specialist status the faculty has become the proud owner of banks of PCs, digital cameras and state of the art software. But when I decided to introduce photography in year 7 we possessed a single camera, one computer and a copy of Adobe Photoshop Limited Edition. I wanted to devise a way of getting the pupils to really look at pictures, to engage with them, and make images of their own that they would be proud of. In order to overcome the management difficulties of having only a single camera, I integrated the photographic element within a broader project on the theme of identities. The pupils drew themselves and one another, experimented with different media, produced collages and wrote about their lives. I generated an atmosphere in the studio (never referred to as a classroom) where the pupils could feel comfortable working on different things to their peers. But the core of the project was the idea of creating a photographic portrait, based on a specific genre and inspired by the work of the American artist, Cindy Sherman.

We started by looking at her work. The pupils investigated her approach and inspirations. They were introduced to the digital camera. Working in small groups, with the aid of a tripod and a couple of desk lamps, each took a few photographs of the others, experimenting with different angles and lighting. They were asked to explore the various moods they could create by cropping, lighting the subject from below or above and changing their own position relative to the subject. The photos were printed out, thumbnail size, and the students were encouraged to annotate them, drawing on top of them to express what they felt had been successful and why.

Next we discussed the notion of genre. We looked more intently at Cindy Sherman’s work. What did her photos remind them of? Why did some look like stills from early Hollywood films and others like advertisements in a glossy magazine? How had she achieved these impressions? The pupils were instantly attracted to her work as it was close to images they were already familiar with, which made it easy for them to access.

After this the pupils were divided into four groups. One investigated Film Noir, early black and white movies. Another looked at fashion photography. The third had to research horror film and the fourth were asked to look at painted portraits by famous artists. For homework they began to research their given genre. I asked them to collect relevant images and make notes about what they wanted their own photos to look like and why. They collected together props, wigs, clothing and the make-up required for their work.

Building on the skills they had acquired with the initial experiments, the pupils began working in small groups to create their final images. As the photographs were taken, pupils began to manipulate their images on the computer. I encouraged them to restrict the effects they employed, to concentrate on using a few simple tools, adjusting the contrast, cropping the image, altering the colour balance. The results were astonishing.

It was obvious from the beginning that some genres would be very popular. Every student wanted to pretend to be in a horror film because they loved dressing up! But the greatest affirmation of the project was an incident I observed after school one afternoon. The girls who had been studying the portrait paintings genre to research had asked if they might use the studio after school. Perhaps they were shy about working in front of the others or perhaps – as I like to think – they wanted more time to concentrate.

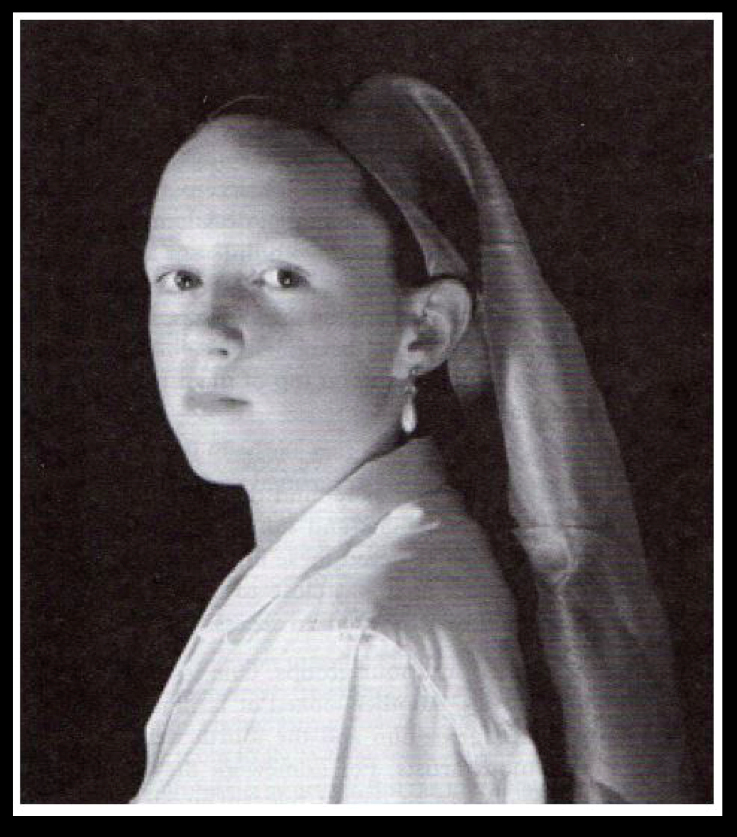

They had chosen Vermeer’s painting, The Girl with the Pearl Earring, as their subject and had raided the textiles room for appropriate fabrics. I had a meeting in a neighbouring classroom so I left them to it. When I returned to the studio some time later, I stumbled into a full blown argument. The girls had not heard me coming back and were disagreeing loudly about exactly where the light was coming from in the original painting. The row was becoming quite heated and I watched, in amazement, as this group of eleven year old girls had a serious and impassioned debate about the light in a painting by Vermeer. I cannot think of another way of achieving such involvement. Their exposure to a contemporary artist whose work they could easily access and roughly replicate had opened the door to an appreciation of Dutch painting from the 17th century.

This story illustrates one of my core beliefs in art education, and even education in general. All human beings have enormous potential. Children all have hidden talents and untapped abilities. Our primary role as educators must be to release this potential. To open the door. But what prevents this from happening, or at least a major factor that stands in the way, is skill, or rather, the perceived lack of it. When a child believes they are no good at something, when they expect to fail, they cannot succeed. This is the biggest barrier to understanding. By allowing year 7 pupils to work with photography to create these portraits I was removing the barrier that trying to draw would have created. It opened the door to a depth of understanding, a door that would otherwise have remained closed. This is not to belittle skills but rather to champion the unleashing of potential and foster the understanding that all children have and give them back their faith in their own capacity to learn.

I have two young daughters and one of the most rewarding things about being a parent has been watching them drawing. Their approach to making things is fascinating. It is amazing to watch them beginning a drawing, confidently integrating all sorts of information, incorporating things they can see and things from their imagination. So what happens? Why can we do this at four but feel so worthless and inadequate by fourteen?

A Guerrilla Approach to Teaching

What is a guerrilla approach? It starts with self-belief and its most important component is passion. I am a painter and I am passionate about art. When I have spare time I devour art books. Apart from my family, they are the first thing I would rescue from my house in a fire. Although I am a painter I have developed a catholic taste. All art interests me. Why is this important? If we are to inspire children, and surely real teaching should be inspirational, then we must first inspire ourselves. One of the most exciting and invigorating things about teaching art is our freedom to introduce and explore just about anything we like. Almost anything that we ourselves are drawn to can form the impetus for a lesson or project. I relish the thrilling brainstorming sessions that began with fellow PGCE students and continue with my colleagues now. Something we’ve read in the newspaper, a TV show we’ve watched, an exhibition we’ve attended or even a CD we were listening to.

So where does planning come into all of this? You cannot plan to be spontaneous. If you are allowing the possibility that a conversation over a cup of coffee ten minutes beforehand can determine the direction a lesson takes, then planning becomes an irrelevance. Planning, that is, of carefully constructed three part lessons, scripted to ensure that the keywords are referred to. But in a sense I’m planning all the time. Constantly looking for new ideas, themes and artists. Constantly being inspired. When you get excited because of a show you’ve just been to see, it comes out. The children see it and it affects them. I believe it’s important to nurture this belief in the pupils. To make them believe that their passions and interests are just as valid, just as important. To encourage them to see themselves as artists. And why not? I am continually astounded by the work that my pupils make. The girls who cast a boy’s face in chocolate and proceeded to take bites out of it. The boy who inserted a cardboard cabinet into a pillow case and filled each drawer with a miniature sculpture based on one of his dreams. The video of a girl falling asleep, speeded up to become an unnerving and unsettling experience for the viewer. The photographic installation based on the signing alphabet. A maze constructed from hundreds of black bin bags. All of it confident and mature work. All of it inspired by contemporary practice, by being immersed in a culture where anything can be art.

What fascinates me about this process is the speed with which the pupils begin to show the confidence to trust their own instincts and ideas. What I think this proves is that they have – that we all have – remarkable imaginations and ideas. By introducing pupils to contemporary practice, by talking to them about the ways present day artists make artwork and by allowing them the freedom to try anything, we nurture that sense of enquiry and willingness to experiment. The results can be outstanding.

So how does this work in practice? To illustrate I shall first describe a scene. A GCSE class, year 10. At a table near the front of the studio a small group of students are busy with some chalk drawings. They are working from microscopic photographs of the body. Behind them a boy is using a hair dryer to soften the wax he is using; behind him his sketchbook lies open, revealing a half-finished relief based on the structure of a human face. Several girls are working on the floor, experimenting with mixing glues and different paints, exploring processes. Two students are sitting at computers, using the internet to research. Another group is working on small, modelled clay figures, each contorted into an expressive pose. Others around the room are busy in their sketchbooks. I am circulating the room, commenting on the work in progress, answering questions, asking questions, suggesting relevant artists, challenging the pupils.

The project is titled Pain, Medicine and the Human Condition. We began by discussing the theme. We looked at artists who have produced work inspired by the body. Contemporary protagonists like Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn, Jenny Saville and Ron Mueck, but also the history of the body and medicine in art, all the way back to Leornardo da Vinci. The first weeks of the project were spent working on activities as a group – directed work, led by me. The pupils produced life drawings of one another and were given a demonstration of modelling a figure in clay. They each produced a small figure, inspired by a specific emotion. They worked on other drawings, from primary sources, like a skeleton or the preserved organs in jars we had borrowed from the science department, and they also worked on secondary sources; photographs in textbooks and existing works of art. We looked at the world of microscopic imagery and compared the pictures to abstract paintings. The pupils made abstract paintings. They were shown the work of a range of process painters and experimented with different materials to create work of their own. All the time the pupils were encouraged to question the things they were looking at, to analyse the activities. If they showed signs of wanting to explore something further, or expressed a desire to develop an aspect of the work in a different way, they were encouraged to do so.

By the time we reach the point of the scene described, the pupils are working independently. Most are developing the confidence to trust their own ideas and are actively engaged in the subject and theme. One girl has started making work inspired by a piece of writing she asked her brother, who suffers from arthritis, to produce. Another, after coming across the work of Sarah Lucas, has sculpted a pair of lungs in clay and is now busy decorating the surface with cigarettes. One pupil is using the photographs he took of his broken ankle, a football injury. They have ownership over their work. They are excited by what they are doing, and so am I. But what about the pupils who are not yet capable of doing this, the pupils who have not yet built up the confidence and independence? The structure of the project, with its introductory period of directed activities, provides a safety net, a safe zone. All the pupils have been given options they can readily pursue. The difference with this approach is that it opens another door. A door that can lead wherever they want it to.

There is no doubt that this guerrilla teaching is taxing for the teacher. Logistically it can be a nightmare to organise, resource and manage. When you potentially have clay, plaster, charcoal, video editing and painting all going on in the studio at once, things can get out of hand. Chaos can reign. Sometimes I feel as though I’m spinning plates, or that I am hanging on by my fingernails. Teaching would be an easy job if all the pupils filed in and did the same thing, at the same time in the same way. But that would make teaching an unrewarding job. I think I can excuse the odd blocked sink, the occasional explosion of plaster on the floor, paint stains on the tables.

The alTURNERtive Prize

I wanted to start my pupils thinking about art in a different way. To consider the impact it has on society and the affect it can have on the viewer. There is so much art made in schools, and most of it goes unnoticed. Yes, art rooms have things on the walls and most schools strive to put things up in the corridors, but it is rare for a school to have a forum in which concepts of exhibition can be explored. At Welling School we are blessed. We have a beautiful purpose built gallery, spacious and well lit. Over the past three years we have been building a programme of exhibitions that allow the pupils, staff, parents and local community access to the work going on in the school. At the core of this programme has been the alTURNERtive Prize.

I set up the prize in November 2002, timing it to coincide with the Turner Prize (3) at the Tate Gallery. I wanted pupils to be aware of the relevance that contemporary art has in society. I asked teachers to nominate pupils from years 10, 11, 12 and 13 who they considered actively engaged in a contemporary approach to making art. We sorted through and came up with a shortlist of students who were invited to submit work for the exhibition. The work covered a broad range of practice. We had paintings, photographs, sculpture and video work. We printed posters and invitations, held a private view, and announced the winner, a year 11 girl who had created a video piece based on a missing person. She had drawn around her friend’s body in the playground after school one evening. Then the next morning she arrived early and set up a camera to film the pupils as they came into school, to capture the mixture of bemusement and incredulity at the apparent murder scene. When edited together the final result was both humorous and moving.

Over the following weeks we took groups of year 7, 8 and 9 pupils around the exhibition. Sometimes the pupils involved in the show would operate these tours, explaining their work and fielding questions. This helped to build their confidence and has inspired tremendous interest in the subject lower down in the school. It’s one thing to be excited about a piece of work made by a practicing artist but quite different and perhaps more profound to be inspired your peers.

For the 2003 exhibition, I made a documentary about the nominated candidates. Each pupil was asked questions about the work they were submitting and their plans for the future. The resulting footage was screened at the exhibition. The shortlist was smaller this time to allow each pupil to display a more substantial body of work. The winner ended up showing three pieces in three different media, including a five foot square painting of his own head, constructed from 10,000 acrylic fingerprints.

Making the documentary and interviewing the pupils changed the way that both they and the viewers who came to the exhibition looked at the art. They started to question what things meant, and in particular how the context in which things were seen could affect their meaning. Having a gallery on site allows the pupils to experience art first hand, as well as the opportunity to curate their own shows. They see exhibitions as just another facet in their lives, along with TV, shopping, magazines and Playstation games.

Conclusion

Contemporary art practice is proving to have a profound impact on my pupils. Whereas art often seemed an elitist activity even a few years ago, an awareness of contemporary artists, and the freedom to experiment in a similar way, seems to be allowing more students to access the subject. By enabling them to create sophisticated work by means of a broad and ever expanding range of media, they are realising their creative potential.

We must champion this in formal art and design education in schools. All children should be given the opportunity to unleash their potential, and the curriculum should be led by them. We need a more child centred approach, a more flexible approach. We must give pupils the space to both understand and develop their imaginations. We need to be brave as educators, to risk failing and creating chaos in order to allow things to take unexpected courses. A guerrilla approach to classroom teaching encourages pupils to pursue their own paths, with the teacher following and helping where they can, inspiring, questioning and facilitating; enabling the pupils to create works of art for themselves.

- Specialist status: Schools in Great Britain are being encouraged to opt to become specialist in a particular curriculum areas, e.g; Sports, Languages, technology and Visual Arts. This means that they are able to put more emphasis on that area of the curriculum, but are still required to deliver the curriculum as a whole.

- PFI: The Private Finance Initiative was set up by the government as a way of injecting large sums of money into state institutions such as hospitals and schools. Private businesses are invited to fund the rebuilding of such institutions. In return they manage the building, leasing it to the incumbents, but also being permitted to raise income by other means such as private hire of facilities.

- The Turner Prize: An annual competition set up in 1984 by the Tate Gallery, intending to highlight the best young British art. Nominees have to be under 50.

Published in “Social & Critical Practices in Art Education” Edited by Dennis Atkinson and Paul Dash. Trentham Books. 2005